Assyrian References in Modern Near Eastern Literature

(Part 2 of 2)

Stan Shabaz

Washington, DC

In the first part of this essay, I reviewed some trends in early modern Near Eastern literature. Starting in the later half of the 19th century, historical fiction became an important and popular regional genre. There seemed to be a thirst for stories based on historic civilizations and personalities. But, as was noted, there was a relative lack of stories based on Assyrian and Mesopotamian themes.

Political and Cultural Essayists

Yet, while not a major motif in the historical fiction of the era, there was a genre where Assyrian references were more prominent. Ancient Assyria was referenced in some of the socio-political essays of the era. Ameen Rihani discusses Assyria in a more political vein in his essay “Under the Yokes of the East and West” [1]. In this essay he describes the relations between the Phoenicians and the Assyrian and Babylonian empires. In regards to the Assyrians he states that “Assyria’s yoke was an awful yoke.” He goes on to write:

At that time, the Phoenicians oscillated between Babylon and Egypt, offering their loyalty to the more powerful of the two countries. When one became weak, they transferred their loyalty to the other more powerful king. […] They were all milk and honey to Nebuchadnezzar and they were bitter to the pharaoh. The next day, the situation would be different. It would carry honey to Egypt’s throne and vinegar to Babylon’s throne. […] Phoenicia lay between the devil and the deep blue sea, as the English saying goes. […] O Egypt, O Babylon, what is the winged sun and the winged lion? The fire and den are one and the same.

So we see that Ameen Rihani expressed reservations regarding the power of ancient Assyria. But we must understand the era in which he was writing. The Levant was just emerging from a very bitter and brutal war ending the last stages of the Ottoman Empire’s control of the region. The liberation from the Ottoman Empire came at a very high price. [2] After sacrificing so much, the people of the region were extremely sensitive to any threat to their hard won freedom. Thus, Rihani’s point was more aimed at the dangers of imperial powers in general and modern imperial powers in particular, than at Assyrian civilization per se. For, in fact, Rihani greatly admired the glory and power of the Assyrian empire. In his book, “The Path of Vision”, Rihani states that:

after all, Nineveh and Babylon might only be asleep. To be sure, wherever there are streams of opalescent water, human life is imperishable, immortal. But sleep is often mistaken for death; and the apoplexy of a nation is of longer duration than that of an individual. Under the magic wand of modern industrialism, therefore, Babylon and Nineveh might rise again and put Paris and New York to shame.” [3]

He expresses similar sentiments as to the greatness and glory of Assyria and Babylon in his poem “Tigris” which he composed in 1922 while visiting Baghdad.

Charles Corm and Michel Chiha

Another writer of the era and friend of Rihani’s [4], Charles Corm, also has references to Assyria in his epic poem the “La Montagne Inspirée” [5]. Unlike Rihani, Corm’s references are more symbolic and stylized and less overtly politico-historical. Corm alludes to the similarities between the mythological narratives of Mesopotamia and those of the Phoenician coast. But Corm also touches upon a modern era connection as well, when he expresses “deep sadness” over the loss of the Syriac linguistic heritage:

Such sadness, sadness, unspeakable sadness! Our grandmothers spoke Syriac in Ghazir [6] […] The language of yore is forever silenced in our thin throats.

Noteworthy is the fact that Corm, a noted Francophone writer and dedicated Francophile (even to the point of dedicating his book to Maurice Barrès [7]), in this poem expresses a rare moment of unease with the famed multi-lingualism [8] of the Levant. This “philological flexibility” [9] was usually a source of great pride for Corm as well as for his friend and associate Michel Chiha [10]. Both Corm and Chiha recognized the necessity of this innate multi-lingualism for commerce, cosmopolitanism, cross cultural understanding, and, especially in the case of Chiha, for mercantilism. Perhaps this could be seen as a minor point of divergence between Corm’s philosophy of Phoenicianism and Chiha’s philosophy of Mediterraneanism. [11] Due perhaps to the Chiha family’s history and importance in international banking [12], Michel Chiha emphasized the absolute necessity for the country to always remain multi-lingual and conversant in all the living languages of trade and commerce. Corm also viewed this multi-lingualism--especially when it came to French--as a source of pride. Yet, in this instance, however, Corm expresses regret that our own ancient indigenous languages have been neglected in favor of the modern languages of world trade, culture and commerce. He mourns the loss of facility in the Syriac language and despite being a distinguished Francophone poet he actually uses the term “tyrannical sweetness” to describe the French language. Corm writes:

For the Italian, Greek, British, Turkish and Armenian

Idioms burden her [Mount Lebanon’s] process,

While she gives herself to the tyrannical sweetness

Of the French language.

I know though that in London, Paris and Rome

Our writers shall never have their place

And that everywhere they go, albeit as men they shall be

outside of humanity.

How a people is orphaned when they are language-less

How the languages of others are but borrowed clothes

How we look uncertain, shameful, sickly, bloodless,

strange and obtrusive!

How we seem like intruders at a private party,

Even when we come full of good intentions [13]

Jubran Khalil Jubran

Kahlil Gibran (Jubran Khalil Jubran) also has a few references to Nineveh and Assyria. But, as in the case of Rihani, they are mainly allusions to the evils of empire. For example, in “We and You” he states, “You have built Babylon upon the bones of the weak, and erected the palaces of Nineveh upon the graves of the miserable.” And in “Slavery” he writes “I have followed man's path from Babylon to Paris, from Nineveh to New York [14] Everywhere beside his footprints in the sand I saw the marks of his dragging chains”. [15]

So basically, Gibran seems to regard Babylon and Nineveh as the ancient Souraqian [16] equivalents of the modern world metropolises of New York and Paris. And despite being a modernist, Gibran always felt that the modern urban city was a cold and lonely place and he yearned for the warmth and communalism of his homeland. He felt that the modern metropolis [17] is materialistic, harsh and imperial; its power built on the backs of people who become commoditized and divorced from nature, community and even their own humanity. His critiques of Nineveh and Babylon as the archetypal metropolises of the ancient world reflected some of this unease and loneliness which he experienced while living in the modern metropolis of New York.

But it would be wrong to take these comments as a slight against the grandeur of Nineveh and Babylon. Again, as in the case of Rihani, these comments are more of an allusion to the fleeting nature of imperial power. His references must be seen in this context. That Gibran had great admiration and respect for Assyria, and for Mesopotamian cultures in general, can be seen in his use of Assyrian motifs in his drawings, as well as some of his remarks made to friends. For example, in a letter he wrote to May Ziadeh, Gibran wrote: “I have a special fondness for everything Chaldean; the myths of the Chaldeans, their poetry, their prayers, their geometry, even the minutest relics time has left behind of their art and crafts, all these stir distant and mysterious memories within me, transporting me to days gone by and allowing me to see the past through the window of the future.” [18] And of course his great respect and use of mythological motifs particularly Ishtar and Tammuz, which is a common heritage of the Fertile Crescent from Mesopotamia to the mountain coastland of Gibran’s homeland and even unto Cyprus, the legendary birthplace of Aphrodite, who is none other than our Ishtar.

Tammuz

In later years the Tammuzi literary movement would make much use of these ancient mythological motifs. Poets and writers like Adunis, Khalil Hawi [19], Yusuf al-Khal, Khalida Said, Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, Halim Barakat, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Fu’ad Sulayman, Salah Labaki, Ounsi el-Hage and many others would make use of the mythological and spiritual patrimony of the Fertile Crescent in their works. Themes of death and resurrection would find their way into these works, alternately in the form of Tammuz, Lazarus and Christ [20]. Allusions were made to the triumph over death symbolized both by the phoenix as well as the crucifix; concepts of martyrdom, redemption and salvation filled the works of these writers. They emphasized national and societal resurgence, renaissance and transcendence from a stagnated “wasteland” [21] to a renewed era of dynamism and intellectual creativity. As Adunis writes:

Yesterday, Phoenix, yesterday someone

died on his cross

His light faded away then his

fire-glow returned.

[…]

From the ashes and the dark

it became glowing.

He has as many wings as

the number of flowers in our country,

the number of days and years

and stones.

Like you, Phoenix, his love

overflew; he felt our hunger

for him and died. He died

spreading his wings, putting in

his bosom even those who

burned him.

[…]

Phoenix, this is the moment of

your new resurrection:

What is like the ashes became

sparks, heavenly fire.

Spring returned to the roots

in the soil,

removed the sand of our past… [22]

And heralding this new era of transcendence he writes:

And blood fertilizes life. Nothing will

grow but truth and beauty. [23]

Conclusion

Thus we see that whether in historical fiction, political essays or modernist poetry trends there is a constant tendency to harken back to the ancient civilizations that once ruled the Near East. While some of these attempts may have relied more upon stereotyped and exaggerated caricatures than on actual historical accuracy, one can still discern an earnest attempt to mine the treasures of our ancient epics and myths in attempt to connect the issues of the present with the echoes of our noble ancestral past. It is a trend that should be heartily encouraged. It is hoped that future writers will pay more heed to the greatness of the Assyrian historical legacy and its contributions to uplifting the souls and the minds of humanity; for ancient Assyria was more than just an empire, it was a bastion of culture and civilization and the embodiment of a Higher Ideal that gives true meaning to the lives of men and nations alike.

Notes

- Ameen Rihani, “The Heart of Lebanon” (“Qalb Lubnan”), p. 443-444

- Rihani’s homeland suffered terribly during that war. The Ottoman forces blockaded the entire Levantine coast and encircled the region with troops. It is estimated that half of the population of Mount Lebanon starved to death in the ensuing famine. Estimates of total deaths range from 150,000 to 300,000 in Lebanon alone. On this subject Kahlil Gibran had written: “My people, the people of Mount Lebanon, are perishing through a famine, which has been planned by the Turkish government. 80,000 already died. Thousands are dying every day. The same things that happened in Armenia are happening in Syria. Mt. Lebanon, being a Christian country, is suffering the most. […] I cannot sleep nor rest. All the Syrians here are being tortured in the same way. We are trying to do our best. We must save those who are still alive. Oh Mary, it is too much to bear, too much. Pray for us…” (Letter from Gibran to Mary Haskell, May 26, 1916).

- Ameen Rihani, “The Path of Vision”, pg. 102.

- Ameen Rihani dedicated his book, “The Heart of Lebanon” to: “my friend Charles Corm”

- Charles Corm, “The Sacred Mountain” (“La Montagne Inspirée”)

- Ghazir is in Mount Lebanon. It was the birthplace of Emir Bechir II.

- Maurice Barrès (1862-1923) was a French writer and politician and figurehead of French nationalism. Corm’s dedication reads: “In memory of Maurice Barrès who understood because he loved us.”

- This linguistic facility was even remarked upon by the Jesuit scholar Henri Lammens who praised the “polyglotism and philological flexibility” of the Levant and regarded it as a “badge of distinction and superiority”. Henri Lammens, “Evolution Historique de la Nationalité Syrienne”

- See above note.

- Michel Chiha was Chaldean on his father’s side whose family was originally from Mesopotamia. Michel Chiha is considered one of the fathers of the Lebanese Constitution.

- Said Aql would incorporate some of the ideas of Corm and Chiha and add much of his own thought as well to take these various concepts to a whole new level, even to the point of inventing a new alphabet.

- Chiha envisioned Lebanon as an entrôpot state, a “merchant republic” and safe harbor for capital from throughout the Mediterranean and Arab worlds. (Refer to Kamal Salibi’s , “A House of Many Mansions”, pg. 179.) Thus he always believed in the importance of close cooperation between all the countries of the Mediterranean basin; he believed that international cooperation and commerce must be allowed to flourish freely, unhindered by excessive state interference. While firm in his defense of Lebanon’s independence, he was nevertheless wary of any plans to isolate the country from its broader Mediterranean and Arab environments. Along these lines, he was also adamantly opposed to Zionist plans to create a Jewish state in Palestine. He believed that Israel was a threat to Lebanon, to the Mediterranean region, as well as to the entire Arab World. In a very prescient statement, he wrote in 1947 that “the decision to partition Palestine by creating the Jewish State is one of the most serious mistakes in contemporary politics. The most surprising consequences are going to result from an apparently small thing. Nor is it offensive to reason to state that this small thing will have its part to play in shaking the world to its foundations.” (emphasis added), Michel Chiha, “Palestine”, 1969.

- Charles Corm “The Sacred Mountain” (“La Montagne Inspirée”), pg. 101. These emotional and powerful lines betray a sense of alienation common to Mashriqi writers regardless of political persuasion or sectarian affiliation. They reflect a shared sense of longing for understanding, acceptance and respect that transcends political and sectarian partisanship, and are evocative of the innate Levantine spirit striving to carve out a unique socio-cultural space in a world seemingly intent against this resurrection of our indigenous ancestral identity.

- It is interesting that both Gibran and Rihani compared the ancient cities of Babylon and Nineveh to the modern cities of New York and Paris. See Rihani quote above.

- A similar attempt to use the Assyria Empire as an allusion to militarism can be found in Abdul Wahab al-Bayati’s “The Birth and Death of Aisha” which begins “Ashurbanipal loved me. For my love he built me a city […] He was destiny: a storm and an axe falling on the skulls of kings, on fortresses and cities. He loved me – alas, I had no love for him. For that, trees withered and died, the Euphrates dried up”. Towards the end of the poem we read “I see Ashurbanipal stabbing the sun with his spear. I see the prisoners of war hanging from the gallows at the frightening darkness of dusk.” It is interesting and somewhat disappointing to see how attempts to critique contemporary forces---dictatorial Arab regimes in the case of al-Bayati and the Ottoman Empire and Anglo-French imperialism in the case of Gibran---tend to allude to the ancient Assyrian empire in order to point out the futility of militarism, imperialism and power politics. This despite the fact that it was the ancient Assyrians who united the Near East, facilitated the flowering of a unique socio-cultural regional synthesis, and created beautiful works of literature, sculpture and architecture.

- “Souraqia” was a term occasionally used by Antun Saadeh to refer the Fertile Crescent. References to Assyrians can be found in many of Saadeh’s works including “The Ten Lectures” (“al-Muhadarat al-Ashr”) and “The Rise of Nations” (“Nushu' al-Umam”). Farid Nuzha’s journal “Asociacion Asiria” published in Argentina also contained information on Saadeh. See, for example, special issue July-August, 1940.

- On the subject of modern urban life, Gibran has written: “Oh people of the noisesome city, who are living in darkness, hastening toward misery, preaching falsehood, and speaking with stupidity…until when shall you remain ignorant? Until when shall you abide in the filth of life and continue to desert its gardens? Why wear your tattered robes of narrowness while the silk raiment of Nature’s beauty is fashioned for you?” (Kahlil Gibran, “Yesterday and Today”) It is interesting to compare Gibran’s ambivalence towards the modern city, which he feels is cold and materialistic, and his yearning for the simpler, rural life and contrast that with later regional writers, especially women, who expressed exact opposite feelings: that the modern city was a place of freedom and opportunity liberating them from the confinements of rural life and chafing traditionalism.

- Letter to May Ziadeh, 11 June 1919. In this context, “Chaldean” should be taken as referring to the whole of the ancient Mesopotamian civilizations in an inclusive sense. The Near Eastern essayists of this era tended to use the terms Assyria, Chaldea, and Babylon interchangeably. On this subject, Hormuzd Rassam has written that “ ‘Chaldean’ and ‘Assyrian’ were synonymous words, and the nation was sometimes known by one name and sometimes by the other. Take, for instance, the words ‘English’ and ‘British’ which are frequently used one for the other.” (“The Thrones and Palaces of Babylon and Nineveh from Sea to Sea: A Thousand Miles on Horseback” by John Philip Newman, p. 371)

- Khalil Hawi (1919-1982) born in Shweir. He committed suicide on June 6, 1982, the day the Israelis invaded Lebanon, stating: “How can we wipe out this historic shame?”

- References to Christ in Near Eastern literature are numerous, in most cases emphasizing the indigenous Levantine nature of Christianity and elucidating the cultural context in which the Gospels were written. In this regard the following works are especially important: Abraham Mitrie Rihbani, “The Syrian Christ”, 1916; Kahlil Gibran, “Jesus the Son of Man”, 1928; and George M. Lamsa, “Gospel Light”, 1936. Also important is this regard is “The Life of Jesus” by Ernest Renan, which emphasizes the nature of Galilee and its influence on the spirit of early Christian thought and practice. Renan writes: “Galilee […] was a very green, shady, smiling district, the true home of the Song of Songs […] In no country in the world do the mountains spread themselves out with more harmony, or inspire higher thoughts. Jesus seems to have had a peculiar love for them. The most important acts in his divine career took place upon the mountains. It was there that he was most inspired; it was there that he held secret communion with the ancient prophets; and it was there that his disciples witnessed his transfiguration.” Elsewhere in his book, Renan states that “the people [of Nazareth in Galilee] are amiable and cheerful; the gardens fresh and green. Anthony the Martyr, at the end of the sixth century, drew an enchanting picture of the fertility of the environs, which he compared to paradise […] But the beauty of the women who meet there in the evening—that beauty which was remarked even in the sixth century, and which was looked upon as a gift of the Virgin Mary—is still most strikingly preserved. It is the Syrian type in all its languid grace.” (emphasis added) Renan then sharply contrasts Galilee with Judea: In opposition to the “charming” and “delightful” Galilean spirit, Renan uses terms like “solemn”, “insipid”, “arid”, “somber”, “obstinate”, “hypocritical” and even “atrabilious”(!) to describe the nature of Judea dominated by the Pharisees. Renan also makes note of the term “Galilee of the Gentiles”, pointing to the Syrian, Phoenician, Greek and Arab population of Galilee during Christ’s time. George Lamsa also emphasizes the Assyrian origins of the population of Galilee throughout his book, especially in the section entitled “Galilee of the Gentiles”. “Gospel Light”, p. 22-24.

- Many literary critics have noted an influence from T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land”.

- Adunis, “Al-Ba’th wa-al-Ramad” (“Resurrection and ashes”)

- Adunis, “Qalat al-Ard” (The Earth Said)

Bush: The Destroyer of Christians

Frank Schaeffer

The Huffington Post

16 October 2007

Australian mercenaries working for Americans recently gunned down two innocent women who were members of the Christian minority in Iraq. The meaning of this fiasco should not be lost on us. The fact that the Christian women were shot is part of an underreported "small" tragedy within the gigantic tragedy of the destruction of Iraq. (Full disclosure; my son was a Marine from 1999 to 2004 and was deployed several times to the Middle East.)

Bush is an evangelical Christian. And without the evangelical vote he would not have become president. So it might seem ironic that Bush is personally responsible for the persecution, displacement and destruction of the one million, three hundred thousand-person Christian minority in Iraq. (They fared much better under the secular regime of Saddam Hussein and, along with a handful of Christians in Lebanon and Syria, represented one of the last ancient non-Islamic communities left in the Middle East. According to the Times the community has been almost completely displaced and driven from Iraq following the American invasion and the civil war we unleashed.) But actually Bush's destruction of his fellow Christians is not ironic, because to Bush the Iraqi Christians (including those killed women) weren't "real Christians." According to the theology that has shaped Bush they, like their Muslim counterparts, were part of the "other."

Theology matters. And the theology of the President matters when it comes to trying to understand his behavior. Perhaps you have to have been there, done that in order to understand.

I was raised by evangelical missionary parents (Francis and Edith Schaeffer) who also happened to have quite a bit of personal interaction with the Bush family and other Republican leaders. Mom and Dad often met with presidents Ford, Reagan and Bush Sr. and stayed in the White House several times in their capacity as evangelical gurus to the powerful.

Evangelical theology is inextricably linked to the Bush presidency. And evangelicals hold to a born-again world view. To Bush-the-evangelical those murdered Christian women and all the other non-evangelical Christians in Iraq (Armenian, Syrian Catholics, Orthodox and others), are not "saved" because they aren't born-again. Rather they belong to a tradition that sees salvation as a journey undertaken within a liturgical community of faith, not a one time magical individualistic experience.

In public Bush would never call all non-evangelicals lost, nor would many media-savvy evangelical leaders, but the outlook of evangelicals is one of dividing the world into "us" and "them." And non-evangelical Christians are "them" just as much as any other "lost." How could it be otherwise when the bedrock of evangelical theology is to regard anyone who has a different theology than you -- even within the competing historic Christian traditions -- as "unsaved"?

Pat Robertson expressed the evangelical Bush-type theology a few years ago when he dismissed Eastern Orthodox Christianity as just so much "mumbo-jumbo." To the born-again only a Billy Graham-type of one-time salvation experience counts. People who merely continue practicing the ancient traditions of the Church, people just like those Armenian women the mercenaries carelessly shot down, aren't like "us." That belief explains why evangelicals are busy trying to evangelize Greek and Russian Orthodox, Roman Catholics and "liberal" Christians with the same vigor they apply to proselytizing Hindus or Muslims. And that explains why there has not been a massive evangelical outcry against Bush's destruction of the Iraqi Christian community.

According to Bush's theology he has in fact not destroyed fellow Christians. To Bush and other evangelicals the word "Christian" refers only to evangelicals. In the common parlance within the evangelical subculture, "becoming a Christian" is just another way to say that someone has become an evangelical.

The "us" and "them" mentality is instilled in every born-again believer. To evangelicals there are actually two human races; the "sheep" and the "goats" in other words us and them. And the "them" includes all non-evangelical Christians.

Evangelicals may have given up most traditional formal sacraments in favor of a personalized faith but they have developed their own "sacraments." One bedrock sacrament is the aggressive evangelism of the "lost," including all non-evangelical Christians.

The fact that Bush has managed to complete the work of radical Islam, and smash one of the last bastions of Christianity in the Middle East, is just fine with evangelicals: the destroyed people weren't real Christians, just more of those mumbo-jumbo types. It isn't as if we hired those Australians to shoot our fellow believers at some Billy Graham crusade! The murdered women were on their way to see their priest and they wouldn't have needed all that "priest stuff" if they only had accepted Jesus into their hearts and become real Christians like us.

Frank Schaeffer's memoir, "Crazy For God - How I Grew Up as One of the Elect, Helped Found the Religious Right, and Lived to Take All (or Almost All) of It Back," went on sale on October 26. Frank Schaeffer's memoir, "Crazy For God - How I Grew Up as One of the Elect, Helped Found the Religious Right, and Lived to Take All (or Almost All) of It Back," went on sale on October 26.

The Assyrian Community of Verin Dvin

Courtesy of the Hetq Online

29 October 2007

By Hasmik Hovhannisyan

Translated to English by Hrant Gadarigian

Yerevan resident Susanna Kalashyan had just been promoted to the 8th grade when she was “stolen away” on the way to the school. Her “abductor” was an Assyrian from the village of Verin Dvin. More than forty years have since passed. Susanna has four children and eleven grandchildren. Her husband has long since passed away.

While Susanna understands Assyrian quite well she doesn’t speak the language. “I really wanted to learn my husband’s native tongue but whenever I tried to speak it I’d get tongue-tied, she recounts. My speaking Assyrian just wasn’t in the cards.” Susanna’s husband never forced her or the children to communicate in Assyrian. The three eldest children identify with their Assyrian roots just as matter-of-factly as they relate to their Armenian ones. As for the youngest son, Susanna says he’s Assyrian to the very core. The boy devotes all his free time to the study of Assyrian culture and history.

The largest Assyrian community in Armenia lives in the village of Verin Dvin, located in the marze (province) of Ararat. 2,000 of the village’s total population of 2,700 are Assyrian. Marriages such as Susanna’s aren’t rare in the village. Mixed Armenian-Assyrian marriages are fairly widespread. While strolling the streets of Verin Dvin you get the feeling that you’re not in Armenia. That’s because everyone speaks Assyrian. Both Assyrian and Armenian students are required to take a class that integrates the Assyrian language, literature and history up till the 11th grade. In all else, Assyrians differ little from Armenians. Both peoples share similar customs, family values and lifestyles. Assyrians are quite at ease when it comes to integrating into the Armenian mainstream.

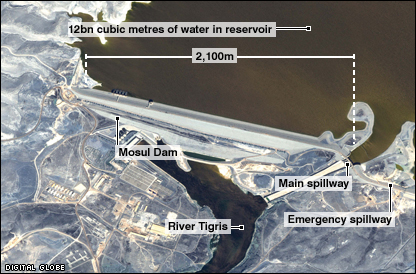

Image courtesy of Google Earth

Image courtesy of Google Earth |

In the view of Meline Tamarazova, the Mayor’s Secretary, “This is quite natural. When is it that a nation strives to preserve its identity? When it’s being persecuted in the diaspora. When relations are amicable, the assimilative process takes place quite on its own.”

Relations between Armenians and Assyrians, at times friendly, at times hostile, date back thousands of years. However Assyrians first appeared on the territory now comprising present-day Armenia essentially in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The first large wave came in 1828, with the signing of the Treaty of Turkmenchai that declared an end to the war between Russia and Persia. Large numbers of Assyrians relocated from Persia to Russia and some of them eventually to Armenia. The second large wave came from the Ottoman Empire during the period of the Armenian Genocide. Large numbers of Assyrians, estimates range from 275,000 to 700,000, also perished during these years. Assyrians fled to this side of the border along with Armenian refugees with the assistance of General Andranik.

Some 7,000 Assyrians lived in Armenia, mostly in the villages of Verin Dvin, Dimitrov and Arzni, up until independence was declared in 1991. Many have now left to work mostly in Russia and Ukraine where, “everything is much less expensive and the exchange rate of the U.S. dollar is higher.” A large segment of the residents of Verin Dvin are now to be found in the Ukranian village of Kakhovka where they’ve established the settlement of “Little Verin Dvin”.

If you visit Verin Dvin during the daytime you’d think only children live in the village. The adults go to the fields to work in the morning and only return after dark. Once school is over for the day the children also go to the fields to lend a hand. The “fields” are basically kitchen-garden plots where the villagers grow the essential household table-fare, rarely selling the produce.

Susanna complains that classes at the village Russian school, named after the writer Pushkin, have been cut from 45 to 40 minutes so that the children can get to the fields in time to assist their parents with the crop harvest. Almost all of the 28 children in her 16 year-old granddaughter Susanna’s classroom go to the garden plots to work, some missing school for days on end. Susanna never allows her grandchildren to miss a day of class.

There are two dance ensembles in Verin Dvin; the ‘Niniveh’ group for adults and ‘Arbela’ for the school pupils. If there’s no upcoming performance to prepare for there is almost no dance practice during the autumn months due to the demands of the crop harvest. Sixteen year-old Sona Petrova, a dancer in ‘Arbela’, says that her group mostly performs at festivals devoted to Armenia’s resident national minorities. Sona adds that if the dance ensembles didn’t exist young people would have little to do apart from working in the gardens or in construction; that is if something was being built. This is why most young people seek to leave for the city.

There are 37 residents of Verin Dvin now studying in Yerevan. Most return to the village every day after school lets out. Only those with relatives in the city remain.

Village Mayor Lyudmila Petrova assures us that while Verin Dvin faces the same host of problems as any other village, the government, especially the Regional Governor’s Office of the Ararat Marze, pays particular attention to the village. In the last two years Assyrian language primers have been printed in Armenia. Prior to this these texts were imported from Russia. Promises to pave the roads by next spring have also been made. The building of the village Cultural House, where the Mayor’s Office, the Post Office, the first-aid station and the library are located, is currently being repaired. Preparations are underway to construct a separate building for the Post Office. Lyudmila Petrova hopes that one day the clinic will also be housed in separate premises. This is one of the major issues confronting the village. While the clinic is outfitted with good technical equipment and has one doctor and three nurses on staff, its present three- room space just isn’t large enough. For example, due to a lack of space, the gynecological chair remains packed-up and unused.

There are two working Assyrian churches in Verin Dvin. Shara, the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East of Armenia is based on the Nestorian Church, while the Church of Marez follows the Orthodox faith. If Armenia was the first nation to adopt Christianity as the state religion, the Assyrians were the first people to accept the Christian faith as early as the 1st Century A.D. From the beginning, Assyrians professed the Nestorian doctrine that declares that Jesus exists as two separate persons; Jesus, the human being and Jesus, the Divine Son of God. Those Assyrians who migrated to Russia from Persia adopted the Orthodox faith. Those who fled to Armenia during the 1915 Genocide retained their traditional Nestorian religion for a time. Today, Assyrians living in Armenia are either followers of the Orthodox Church or profess Roman Catholicism. In accordance with Nestorian Church tradition only a cross is placed in the Church of Shara, while icons adorn the Church of Marez.

There is no Armenian church in Verin Dvin as there is no need of one. Armenians attend services at the Assyrian churches. Residents of the nearby Armenian village of Nerkin Dvin also participate in church services celebrating the Feast Days of the Assyrian churches (June 14th and July 3rd). Prelate Isahak Tamraz, a young clergyman who came from Iraq several years ago now conducts worship services. The religious holidays of both Armenians and Assyrians are almost the same, the only difference being the days on which certain ones are celebrated.

If you were to ask each and every Assyrian whether they dream of eventually having their own homeland, the response across the board would be positive. As to the question would they move to a newly created “Assyria”, residents of Verin Dvin unconfidently answer, “ That’s really a tough question...after all Armenia is our homeland.”

The Three Essential Issues Facing the Assyrian

Community in Armenia

Courtesy of the Hetq Online

5 November 2007

By Hasmik Hovhannisyan

Translated to English by Hrant Gadarigian

Razmik Khosroev, of Assyrian extraction, is a stage actor with the G. Sundukyan National Academic Theatre and the first representative of the Armenian Theatre to tackle the complex role of Shakespeare’s Richard II.

His play entitled “Asoruhi” (Assyrian Woman), a dialogue between an Assyrian and an Armenian regarding the Assyrian Genocide and the present situation of the Assyrian people in Iraq, performed at the theatre in Artashat, was the first Assyrian production in Armenia.

|

Razmik Khosroev |

He chuckles when he states, “ But I delved into Assyrian history for another reason.” The actor is the last person to be born in the former village of Gyolaysor (trans. Assyrian garden) located in the Khosrov forest. The village, settled in 1833, was razed to the ground on the actor’s birthday, May 3, 1949. This was the only instance, a period during May 1 to May 15, when the Assyrians were persecuted in the Soviet Union. It was a time when the Assyrian movement overseas had gathered momentum and when, naturally, the Assyrian communities both here and abroad were in contact with one another. It was also a period when speaking to a foreigner openly on the street could be perceived as an act of treason to the fatherland.

There were eighty households in Gyolaysor (Qoolyasar). The villagers had moved down into the Araratian plains. Most had relatives in the village of Verin Dvin and relocated there soon after the death of Stalin. 2,000 of the 2.700 Assyrians living in Armenia settled in Verin Dvin.

For a long period of time Razmik Khosroev was a member of the National Minorities Council attached to the Office of the President of Armenia. Currently, he serves as the President of the National Minorities Cultural Center. Our discussion encompasses those issues facing the Center, specifically those problems confronting the Assyrian community.

Mr. Khosroev, given the present situation, what are the immediate issues facing the national minorities in Armenia, particularly the Assyrian community?

Whilst never having political problems, ethnic minorities living in Armenia have always faced educational/cultural issues. Until three years ago there was never an official state policy in Armenia regarding the national minorities. Of course today one still cannot state that a comprehensive policy exists. The organization of one or two festivals devoted to the national minorities does not translate into assisting their cultural identity. The government allocates twenty million drams yearly to meet the cultural needs of the national minorities and we are obligated to distribute that amount amongst eleven ethnic minority communities.

It’s truly a tiny amount and what’s even more ridiculous is that the money must be distributed equitably - the same amount goes to a minority community numbering 40,000 or to one represented by only three households. Many conflicts arise due to this absence of funding. During the Soviet period Assyrian radio broadcasts were quite active, but they shut down after independence was gained. Through our efforts, Assyrian radio is back on the air. However, instead of the weekly one and a half hour program that used to be broadcast, the current program is only forty-five minutes long. Only two people work at the radio station and they receive a combined monthly salary of 13,000 drams.

Why is it that the culture of the national minorities is only represented at festivals?

I have to confess that this is more our fault than anything else. We have always organized national celebrations and song and dance shows in our villages, in our homes. All this needed to be centralized in one location. This is why I place great importance on the creation of the Cultural Center. Our Center organizes a variety of events of which I’d particularly like to mention the one and a half hour “Erebuni-Yerevan” celebration. The small Philharmonic Concert Hall was placed at our disposal for this occasion and all the national minorities put on a stunning performance. This celebration was my first attempt to bring ethnic culture to the city. Obviously, we are confronted with the problem of preserving and developing ethnic culture; especially its development. I view ethnic festivals in the same light as I did fifteen years ago. One of the immediate tasks facing the Center is to change this situation.

What work is the Center carrying out in the realm of education?

I’ve been trying for the last three years to get a law passed regarding ethnic minorities. Many ministries and even parliamentary delegates are of the opinion that the rights of the minority communities are already protected by the Constitution so why, they ask, do we need another separate law? However, I am convinced that there is a need for a specific law on the books that also touches on educational issues. There’s a barrier in our educational system that prevents one from teaching without a pedagogical degree. We ourselves have to train our specialists since there is no institution of higher learning in Armenia where the Assyrian language is taught. We send people to Urmia (in northwestern Iran, where 870,000 Assyrians live). Having mastered the language they return here only to find that they cannot teach in the schools since they do not possess the proper teaching degree. The Khachatur Abovyan Pedagogical Institute is the only institution that assists Assyrians in this matter for which I am deeply grateful to the rector. Those Assyrians who study the language in Urmia are accepted into any of the Institute’s faculties on a correspondence basis. Upon graduation they are granted the right to teach Assyrian in the schools.

Maintaining the language is really very important for Assyrians today. Assyrians are unique amongst all national minorities in Armenia not only because they are one of the most ancient of peoples, but due to the fact that they do not have a government to tackle the problems of language preservation.

After independence, what effect did the conversion of schools to an Armenian curriculum have on the preservation of the Assyrian language?

We have a large village named Artagers in the Hoktemberyan area. Fifteen years ago the schools adopted an Armenian curriculum. In the village today you can hardly find a child who speaks Assyrian. The assimilative process proceeded quite rapidly. Thus we’re in favor of maintaining Russian-oriented schools. Our children graduate from Russian schools and still are able to pass the Armenian language exams with high grades. This year we have seven students. The Russian school is neither a problem for us, or for the Armenians.

Despite the fact that the Assyrians are one of the world’s oldest peoples, it appears that many in Armenia are not only unaware that there are Assyrians living in their midst but that they believe that the Assyrian nation vanished off the face of the earth long ago. Is this perception due to your passivity or to our indifference?

Sadly, this is true. I think that there are several factors at play here. One of the most important is the absence of any Assyrian literature. For successive centuries the Assyrian people maintained their existence on the oral tradition, the spoken word. After the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 605 B.C., Assyrian literature disappeared for all practical purposes and it’s only in the past 10-15 years that attempts have been made to revive it. It was in the early stages of the present war in Iraq that the Ashurbanipal Library and Museum, one of the oldest in the world, was razed to the ground and thus a centuries-old accumulated cultural inheritance was obliterated.

In fact, we’ve only begun to teach the Assyrian language in schools during the past twenty years and it is only lately that such classroom instruction continues till the 11th grade and not just the 3rd, as in the past. It’s truly tragic that one of the oldest peoples on earth is destined to oblivion. Alexander the Great bowed in admiration before the magnificence of the Assyrian culture when he conquered Babylon. The Assyrians brought civilization to the world, script and literature, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, and the first constitution - the Code of Hammurabi in the face of a rock-cliff and which is still studied today in law schools. And what marvelous and wise laws they are. One, for example, states that if a physician injures a patient’s eye with a silver scalpel he is obligated to reimburse the patient to the tune of seventeen silver coins. If this law were ever to be included in any nation’s constitution today, one-half of the specialists would quit the profession.

According to official statistics some 750,000 Assyrians were massacred during the period of the 1915 Armenian Genocide. I know that lately you have been actively seeking to publicize this issue. What’s been the response of the Armenian government?

We have only been able to raise such issues in Armenia during the last ten years. Prior to this, one could not speak of such matters. Of utmost importance is that Armenians recognize the Assyrian Genocide. The government of Armenia has never been interested in placing the Assyrian Genocide in the same context as the Armenian massacres. We’ve repeatedly tried to publicize this matter. Three years a book by my daughter Anahit Khosroev (the youngest PHD at the National Academy) entitled The Assyrian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey and Adjacent Turkish-Populated Areas, was published. This academic publication was one of the first works to be devoted to the Assyrian massacres. Interestingly enough, there were many in the academic community who were uninformed as to this reality. Even Richard Hovhannisian was taken aback and proved to be the first one to invite Anahit to give a series of lectures on the subject in the United States. Our concern is that Armenia raises the issue of these two genocides jointly in international tribunals.

Assyrians, just like Armenians, first set about building a church and their homes afterwards. In Verin Dvin, there’s a working church grounded upon the Nestorian faith. What is the state of relations between the Nestorian Church and the Armenian Apostolic Church?

For Assyrians, as for Armenians, are the most important factors when it comes to self-preservation. There are some 4 million Assyrians living throughout the world today but we’re split into 7 religious branches. You frequently run into people overseas who speak perfect Assyrian but when asked regarding their identity they’ll respond by saying, “I’m not Assyrian. I am a Chaldean or Jacobite” In terms of literature, all books and periodicals are published in the same dialect of Urmia, that more than 400 years has served as the literary version of the Assyrian language. Offshoots, naturally serve to divide the nation. The Holy Tovmas Church in Verin Dvin, which was rebuilt five years ago, is the only functioning Assyrian Church in Armenia today. It was originally constructed in the 19th century out of clay and was near totally in ruins.

In 2001, when the 1700th anniversary of Christianity in Armenia was being celebrated, I proposed to the Catholicos that a joint observance be organized and that the reconstruction of the Assyrian Church be included in the itinerary. He declined and explained that the Apostolic Church didn’t maintain relations with the Nestorian Church. This despite the fact that the Khalt and Yacubian Churches are sister churches with the Apostolic Church. But isn’t it true that religious history intimately binds the Armenian and Assyrian peoples? Prior to the creation of the Armenian alphabet and the translation of the Bible into Armenian, Aramaic was the language for conducting religious services in the Armenian Church. Hakob of Mtsbin (the first person in history who attempted to climb Mount Ararat), who traveled to Armenia with Gregory the Enlightener, and who built numerous churches and schools, was an Assyrian. Bishop Daniel, Zenob Glak and Yeprem Asori were all Assyrian as well.

Nevertheless, how did you go about rebuilding the church?

During the 1700th anniversary celebrations a woman from Switzerland, who was a specialist in eastern churches, approached me. It turned out that she remembered me from one of our theater’s stage tours in Switzerland where I performed in a production of Chekhov’s “Three Sisters”. I took her to see the church ruins and it was then that she informed me that she had brought $10,000 to donate to Etchmiadzin but since many people would give money to Armenian Church she offered me the money instead. That’s how we were able to rebuild the church. We then invited Isahak Tamraz, a clergyman from Iraq, to serve in the church. For the first time in eighty years Assyrians living here prayed in their mother tongue.

Have Assyrians living in Armenia retained any national traditions?

Unfortunately not. What I can do is note some traits characteristic to Assyrians such as the work ethic, vindictiveness, and a deep loyalty to family customs. For example, an Assyrian is capable of murdering his wife in a fit of jealous rage but he’ll never divorce her. As regards marriage or other domestic rituals, they are similar to those practiced by Armenians, except for perhaps immaterial differences. For example, wedding gifts presented by relatives and neighbors are collected in the house courtyard, not inside the house. Till recently the Assyrians, just as the Armenians, placed great importance on the wedding dowry. Let me also mention a custom that in my opinion is an enviable one - an Assyrian girl who masters the mother tongue would only bring half the dowry with her. For me, this is a wonderful custom that serves to preserve the national character. Of course, in Armenia today, this custom is not observed. Everyone speaks such excellent Assyrian that who now pays attention to the dowry?

One tradition, nonetheless, has been preserved. Namely, celebrating the New Year on April 1st.

That’s right. We have been observing the New Year on April 1st for 2,670 years now. When the Euphrates and Tigris rivers overflow their banks, the powerful God Marduk who has no equal in the pantheon of Gods, does battle with Tiamat, the God of the Seas, and defeats him. It was on the occasion of this victory that celebrations first began. One of the most important laws of the Code of Hammurabi speaks to this matter. For fifteen days it was not allowed to punish children, the courts were not in session, one could not punish slaves - everyone was happy, singing and dancing, and praising Marduk.The king abdicated the throne. The rich undertook charitable good deeds. All became equal. These celebrations are called “The Impetuous Days”. When the Assyrians adopted Christianity this pagan holiday, along with many others, was preserved.

Mr. Razmik Khosroev is the father of the well-known Assyrian professor and Genocide scholar, Ms. Anahit Khosroyeva who has worked extensively on the causes and effects of the 1915 Genocide of the Assyrians, Armenians, and Greeks. To read Prof Khostoyeva's article in Zinda Magazine, "The Assyrians Surviving Genocide After World War I" click here. Mr. Razmik Khosroev is the father of the well-known Assyrian professor and Genocide scholar, Ms. Anahit Khosroyeva who has worked extensively on the causes and effects of the 1915 Genocide of the Assyrians, Armenians, and Greeks. To read Prof Khostoyeva's article in Zinda Magazine, "The Assyrians Surviving Genocide After World War I" click here.

The Bible Revisited- Part I

Ann-Margret “Maggie” Yonan

California

Many individuals, religious groups and biblical scholars have been fascinated with the Bible for the last two thousand years, depending on their literary, historical, or religious interest.

The five books of Moses, (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) which constitute the Pentateuch, (meaning the five scrolls in Greek) known as the Torah in Hebrew, have been the subject of much debate, and biblical scholars have conducted hundreds of investigations to determine whether or not Moses did indeed write them, as the ancient world came to believe for so long. Nowhere does the Bible say Moses wrote the five books that have come to be known as “The Books of Moses.” Then how is it that we came to believe Moses wrote these books, and why are they called the Books of Moses?

Many of the investigations that have been conducted over a period of six hundred years, have enabled us to understand what prompted these beliefs to begin with, and how each scholarly investigation led to a different stage

The first stage of investigation into the Bible began in the eleventh century, when most everyone still believed and accepted that Moses wrote the five books, but the investigators suggested that a few lines were added here and there. This debate was mostly initiated by Isaac Ibn Yashush, a Jewish Court physician in Muslim Spain, who pointed out that a list of Edomite kings that appears in Genesis 36 names kings who lived long after Moses was dead, suggesting the writer of the Pentateuch lived after Moses. The response to his conclusion was that Abraham Ibn Ezra, a twelfth-century Rabbi called him “Isaac the blunderer,” and recommended that his book be burned! But amazingly enough, Abraham seemed to have his own doubts about who wrote these five books, and alluded that some of the Biblical passages appeared not to be written by Moses’ own hands because they referred to Moses in the third person, using terms that Moses would not have used, describing places that Moses would not have been familiar with, and using language that suggested another time in which Moses had not lived. Ibn Ezra was not willing to state these opinions in public, and thus wrote, “If you understand, then you will recognize the truth.” In another note relating to some contradictory passages, he wrote, “And he who understands will keep silent.”

In the fourteenth century Damascus, the scholar Bonfils accepted Ibn Ezra’s evidence, but was not willing to keep silent. He wrote, “And this is evidence that this verse was written in the Torah later, and Moses did not write it, rather, one of the later prophets wrote it.” Then in the fifteenth century, Tostatus, Bishop of Avila also stated that certain passages, mainly, the death of Moses, could not have been written by Moses, and that perhaps Joshua, Moses’ successor wrote it. But by the sixteenth century, Carlstadt, a contemporary of Luther, stated that the account of Moses’ death was written in the same style as texts that precede it. This meant that Joshua could not have merely added some lines to a Mosaic manuscript, and raised the questions about what exactly was Mosaic and what was added by someone else.

In the second stage of the process, the investigators suggested that Moses wrote the five books but that editors went over them later, adding occasional phrases of their own. In the sixteenth century, Andreas Van Maes, a Flemish Catholic, and two Jesuit scholars, Benedict Pereira and Jacques Bonfrere, thought that Moses did write the original texts but that later on, writers expanded upon them.

In the third stage of the investigation, scholars concluded outright that Moses did not write the Pentateuch. The first to say it was Thomas Hobbes, a British philosopher in the seventeenth century. Hobbes collected examples of cases where some text would read, “to this day.” This suggested that these were phrases of later writers who are describing something that endured over a period of time. Four years later, Isaac de la Pyrere, a French Calvinist who openly declared that it was certain that Moses did not write the five books of the Bible, citing a verse in Deuteronomy which states, “These are the words that Moses spoke to the children of Israel across the Jordan.” De la Pyrere pointed out that these words appeared to be written by someone in Israel, across the waters of the river Jordan, and Moses had never been to Israel in his life. De la Pyrere’s book was burned and banned, and he was arrested and told that he would have to become Catholic and recant his views to the Pope, and he did!

At around the same time, the philosopher Spinoza, in Holland, published a critical analysis, outlining the problematic passages, and demonstrating they were not isolated incidents that could be explained one by one. On the contrary, they were pervasive throughout all five books of Moses. These were the third person accounts of Moses, which Moses would have never said. For example, in Deuteronomy 34, there is a sentence that reads, “There never arose a prophet in Israel like Moses.” This would obviously indicate that it was someone who lived long after Moses, to be able to qualify such a statement. Spinoza was excommunicated from Judaism and condemned by Protestants as well as Catholics. His book was placed on the Catholic index, thirty seven edicts were issued against it, and an attempt was made on his life.

A short time after that, Richard Simon, a French protestant who had converted to become a Catholic priest, published a book intended to be critical of Spinoza, in which he declared that the Pentateuch had been written by Moses, but some scribes had collected, organized, and elaborated upon the old texts. According to Simon, these scribes had been prophets, guided by the divine spirit. His contemporaries did not want to hear that any part of the Pentateuch was not written by Moses, so he was also attacked and dismissed from his ministerial order. His book was also put on the Catholic Index and he was imprisoned in the tower.

Apparently Simon’s idea that writers of the Pentateuch had assembled these texts out of old sources at their disposal, was an important step on the way to discovering who wrote the Bible, to the extent that it prepared the way to deal with a new item of evidence that was developed in the following century, by three different investigators: The doublet. Simply put, the doublets were the same stories being told twice and in a different manner throughout the five books of Moses. There are two different stories of creation, two different stories of the covenant between God and Abraham, two different stories of naming Isaac, the son of Abraham, two different stories of Jacob’s revelation at Beth-El, two stories of God changing Jacob’s name to Israel, two different stories of Moses getting water from a rock at a place called Meribah, and two different stories of the flood, etc. The most common two different stories were that of God’s name. In one story he was referred to as Yahweh, (the mispronounced Jehovah) and in the other story referring to the deity as simply “God,” or Elohim The doublets lined up into two groups of parallel versions of stories, and each group was almost always consistent about the name of the deity it used. This supported the hypothesis that someone had taken two different old documents, cut them up and pasted them together to form the stories of the Bible. In this manner, the next stage came at a time in which Biblical scholars went about separating the strands of the two old source documents.

In the eighteenth century, three independent investigators arrived at the same conclusion based on such studies. A German minister named H.B. Witter, a French medical doctor named Jean Astruc, and a German professor named J.G. Eichhorn. At first, it was thought that one of the versions of the stories in Genesis was an ancient text, written by Moses himself. Later, they thought that both versions were from old sources that Moses had used to write his work. Eventually, however, they concluded that both of these sources had to come from writers who lived after Moses. As their investigations developed further, each step of the process was leading less and less to Moses himself.

Around the turn of the nineteenth century, this two-source hypothesis was expanded into four! In other words, there were not just doublets, but triplets, then quadruplets. This came about when a young German scholar, W.M.L. De Wette, in his dissertation, hypothesized that the fifth book of the five books of Moses, (Deuteronomy) was different in language from the other four books.

Now we had a working hypothesis by which we can move forward and open the book of Genesis and be able to identify the writings of two, or even three authors on the same page. At this stage scholars knew there was also an editor, (a cutter and paster) who combined the source documents into a single story, and as many as four different authors who contributed to one page of the Bible. Still, no one knew for sure who these authors were, when they lived, why they wrote, and who this editor that combined them was, and why he combined them in the way he did, rather than re-write them.

The evidence, thus far, revealed that four different source documents were combined into one continuous history. The four documents were given an alphabet name. The document that was associated with the divine name of Yahweh/Jehovah was called J. The document that referred to the divine as GOD, (Elohim) was called E. The third document that dealt largely with legal sections and priests was called P. The source that was found strictly in Deuteronomy was called D.

The question now was, how to uncover the history of these documents, who wrote them, what time period they lived, why four different versions, and did each writer know of the other’s existence, how they were preserved, and how they were combined? The first step was to try to uncover the order in which they were written, and what stages of religious development in Israel did they reflect. This approach was the nineteenth century Hegelian method of Historical development of civilization. Two major investigators stand out in this period: One of them was Carl Heinrich Graf, who tried to uncover the order these texts were written, and the other, Wilhelm Vatke, who tried to trace the development of ancient Israel’s religion, attempting to separate early from late stages of the religion.

Graf concluded that the J and E documents were the oldest version of the biblical stories, in so far as they were not aware of matters that were treated in other documents, and that D was later than J and E. Vatke, on the other hand concluded that J and E reflected a very early stage in the development of the Israelite religion, when it was based on nature/fertility, and that D reflected the stage at which the religion of the Israelites was based on the prophets, (the spiritual/ethical stage). He regarded the P document as that which reflected the latest stage of Israel’s religious development, which was priestly, based on priests, ritual, sacrifices, and law.

Both of these two works of Vatke and Graf pointed in the same direction, which proved that the laws and most of the narratives have nothing to do with the times in which Moses lived, much less written by Moses, not even of life in Israel in the days of prophets, and kings of Israel. They were documents written by someone who lived toward the end of the biblical period.

At this point in time, scholars had reached the conclusion that biblical Israel as a nation was not governed by law for its first six centuries, but Vatke’s and Graf’s works came to dominate biblical studies for a hundred years primarily because of one man’s work. This man was Julius Wellhausen, who lived from 1844-1918 and who did extensive research into biblical scholarship. Wellhausen brought the works of all other investigators together and organized them into a comprehensive thesis.

Wellhausen accepted Vatke’s idea of Israel’s religious development in three stages, as well as Graf’s conclusion that the documents had been written in three different stages, and he put the two pictures together. His conclusions were the same as Vatke’s and Graf’s.

Wellhausen began to examine why these various sources existed and his theory of the combination of the two sources began to gain acceptance, and came to be known as the Documentary Hypothesis. In the English speaking countries, the documentary Hypothesis owed a lot of credit to William Robertson Smith, professor of Old Testament in Scotland, because he was the well-respected editor of the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Things began to change in the twentieth century because of Pope Pius XII encouraging scholars to pursue the history of the writers of these documents, to the extent he thought they were “the living and reasonable instrument of the Holy Spirit.” As a result, the Catholic Jerome Biblical Commentary arrived on the scene in 1968, one of the many books, journals, and articles dealing with biblical studies and contributing to modern theological pursuits.

Before 1200 B.C. when the region that came to be known as Israel, was a land inhabited by many nationalities, among which were the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, the Gorgashites, and the Jebusites. The Philistines also shared that land, but they originally came from the Greek Islands.

The land in which the Israelites lived was bordered by Phoenicia in the north. On the Eastern border to the north was Syria, then Ammon, then Moab, then Edom to the south. The 13 tribes of Israel were the largest population in that region, from the twelfth century B.C. on. In addition to the bordering countries, there were influences from Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The dominant religion of the region was paganism, which many to this day believe is idol-worshiping. This view was formerly held until the immense archaeological findings gave mankind a better understanding of the pagan religion, and proved that it was not idol-worshipping as a Babylonian tablet points out. The discoveries at Nineveh alone, which unearthed 50,000 tablets, and in the Canaanite city of Ugarit three thousand more were found, revealing that paganism was a religion of nature, worshipping the sky, the storm, the sun, the sea, and the wind, etc. and it was due to the people being and feeling close to nature. We can compare the statues of these ancients to the icons of Mary and Jesus, found in churches today, but this does not mean they worshipped these icons rather they served to remind the people of the deity’s presence.

The chief pagan god perceived in the Canaan region where all these nationalities lived, was EL. El was male, patriarchal, and ruler over the people. He sat at the head of the council of the gods, (the Elohim) and pronounced the council’s decision. In the northern region of Canaan, where it became known as Israel, and where the majority of the population lived, the Israeli god eventually became known as Yahweh, also male, patriarchal, and ruler over the people. To date, we do not know where the word Yahweh came from, but as biblical scholars point out repeatedly, it comes from YHWH, translated erroneously as “he is who he is, or “I am that I am” and other such unreliable meanings. In Exodus 3:13-15 supposedly Moses asks God what is his name that sends him to speak to the children of Israel, and God says to Moses, “Eheya Asher Eheyeh” translated by the Western translators as “Asher” and written in Arabic as Ashar, but could this be the Akkadian word, ASHUR, the name of the Assyrian God?

Biblical scholars always write, “The People of Israel spoke Hebrew,” but no one has ever been able to define what it is exactly. Is it a language of the people who lived in Hebron? If so, what did the other tribes speak, who did not live in Hebron? As we know the Jews use the Ashuri (Assyrian) script to write, thus how was that different from “Hebrew?”

Among the other nationalities that shared the region of Canaan, Phoenician, Ugarit, Aramaic, and Moabite was spoken. The people in those times wrote documents on papyrus, and sealed them with a stamp pressed in clay. They also wrote on leather, clay tablets, and even stone and plaster.

There are traditions about the prehistory of the Israelites, but none that have been proven through archaeology. According to biblical scholars, the first point at which we actually begin to have sufficient evidence to picture a life of the biblical community is the twelfth century B.C., when the Israelites became established in this territory.

The Israelites’ political life was organized around tribes. According to biblical tradition, there were thirteen tribes. Twelve of them each had a distinct geographical territory. The thirteenth, the tribe of Levi, was a priestly group. The members of the Levi tribe lived in cities in the other tribe’s territories. Each tribe had their own chosen leader. There were others who acquired authority through their positions in society, among which, were judges and priests. The office of judges involved legal matters and military issues. Judges and prophets could be male or female, whereas priests only males. Usually the priests had to be from the tribe of Levi and their office was hereditary. They presided over religious sites, and conducted religious ceremonies, which was mostly sacrifices. Being a prophet did not require a special office. A person from any background could become a prophet, male or female.

The age of judges culminated with the prophet Samuel, who was considered to be a judge, a priest, and a prophet. He lived in Shiloh, a city in the northern part of the land of Canaan, and a major religious center at the time. According to biblical accounts, a tabernacle was located there which supposedly housed the “ark of the covenant” containing the tablets of the Ten Commandments. A distinguished priestly family lived in Shiloh, and some believed they were descendants of Moses. When the Philistine domination of the land became overwhelming, the people sought a leader, who could unite the tribes as a king. Samuel anointed the first king of Israel, King Saul. This was the beginning of the Israeli monarchy, and although there were to be no more judges, there continued to be priests and prophets.

A king needed the support of the priests in order to gain the respect of the people, and to generate an army. There was no separation of religion and state, so that when Saul overstepped his bounds with the priests, Samuel anointed another king, David, who was the ruler of the tribe of Judah. Saul enraged, had all the priests of Shiloh massacred, except for one, which escaped. Saul reigned over the northern Kingdom, whereas David was ruler over his southern kingdom of Judah. Saul maintained the northern throne until his death, when the kingdom was split in half between Saul’s son Ishbaal in the north, and King David in the south, ruling over his own tribe of Judah, which was the largest of the tribes put together. When Ishbaal was assassinated, David became king over the entire country, north and south. King David established a long line of Davidic kingship descended from him. The Davidic dynasty became the longest ruling family of any country in the history, and established the messiah tradition of both Judaism and Christianity.

King David united the two kingdoms and moved his capital from Hebron, (which was the principle city of Judah) to Jerusalem. Jerusalem had been occupied by the Jebusites, before David conquered the city, therefore it was not affiliated with any of the tribes of Israel, hence did not offend any of the competing tribes. David’s second action was to appoint two priests to represent the unity of the two kingdoms: His northern priest was Abiathar, who was the only priest that had escaped the Shiloh priestly massacre David’s southern priest was Zadok, who came from David’s former capital city of Hebron in Judah. Zadok and his priestly order were regarded as descendents of Aaron, the first high priest of Israel. Hence, David’s two priests represented both respected priestly families: The family of Moses and the family of Aaron.

David established a professional army, no longer depending on the individual tribes to muster soldiers. By one military campaign after another, David successfully brought Moab, Ammon, and maybe even Syria, under his dominion. He built a large dynasty and made Jerusalem both the political as well as the religious center of his empire. He brought the “ark of the covenant” there and established his priests there as well. David married many women and had many children, all of whom contended for the throne. But in his old age, David chose Solomon, the son of his favorite wife, Bathsheba, to succeed him.

Biblical sources, in order to embellish Solomon’s wealth, suggest that Solomon had nearly 700 wives and 300 concubines. He married women for political alliances. The Bible also tells us that Solomon built a temple in Jerusalem, in which he placed the ark. The interior of the temple was divided into two rooms, an outer room called the Holy, and an inner chamber called the Holy of Holies. The Holy of Holies was a perfect cube, twenty cubits long, wide and high. In it were two tremendous statues, which could be best described as winged-bulls, like the Assyrian lamasus. They were the throne platform of Yahweh. The ark, containing the Ten Commandments was placed under the Lamasu’s open wings, (which made a tent). Solomon received help for building the temple at Jerusalem as well as his palace from Hiram of Tyre, king of the Phoenicians, who was Solomon’s father-in-law. Hiram provided Solomon the cedars of Lebanon and 120 talents of gold. In return, Solomon gave Hiram a tract of the northern Israelite territory containing twenty cities. In this manner, Solomon was building up his own capital at the expense of the north.

Solomon’s domestic and foreign policy threatened the unity of his kingdom. Moreover, Solomon established twelve administrative districts, each of which was to provide for the court in Jerusalem for one month of the year. The boundaries of these districts did not correspond with the boundaries of the twelve tribes. He personally appointed the heads of each administrative district, which were in opposition to the twelve heads of the tribes. He also instituted the missim system, a sort of labor tax, in which each citizen owed a month of work for the government, each year. This was seen by the people as the same system the Egyptians imposed on the Jews in Egypt, when they were made into labor slaves. Consequently, Solomon was barely holding on to the kingdom, facing resentments and hostilities.

When Solomon dies, his son Rehoboam succeeded him, and he didn’t have the skills of his father to keep the kingdom together. When Rehoboam went to Shechem, a major northern city for his coronation, the northern leaders asked him if he intended to carry out his father’s policies. His answer was yes. They rebelled against him and stoned to death his officer in charge of missim, a signal that they would not be in bondage as they were in Egypt. Rehoboam only ruled Judah, the southern part of the kingdom. The rest of Israel chose Jeroboam as their king. David’s empire now was split again: Israel in the north, and Judah in the south. Rehoboam ruled from Jerusalem, the city of David, and Jeroboam made Shechem the capital of the new northern kingdom. They still shared a common religion, in which both worshipped Yahweh, but the country was divided politically. The temple, the ark, the chief priests were all located in Jerusalem, This meant that on holidays and special occasions, masses of Jeroboam’s population would have to go the city of David, pray and sacrifice at the temple of Solomon, and they would have to see the king Rehoboam, and this did not please Jeroboam. Jeroboam could not make up a new religion, to keep the people from going to Jerusalem. But he could establish for his new kingdom its own national version of the common religion. The kingdom of Israel like the kingdom of Judah went on to worship Yahweh, but Jeroboam established new religious centers, new holidays, new priests, and new symbols of the religion. The new religious centers that were to replace Jerusalem were Beth-El and Dan. His new symbol of the religion became two golden calves, which replaced the Lamasus in Jerusalem. Calves in Hebrew translated into “young bulls,” and they were associated with El, the chief of the Canaanite gods, who was referred to as “Bull El.” This gesture of Jeroboam affiliated Yahweh with El. This might have meant to give the people the impression that Jeroboam was uniting the two kingdoms religiously, by implying that Yahweh and El were one. Jeroboam set-up one of the golden calves in Beth-El and one in Dan, signaling that God is enthroned over the entire kingdom, from the north to the south.

The northern Levites had suffered humiliation and betrayal, because many of them lived in the cities given to Hiram, and of all of them, the priests from Shechem had suffered the most. They had previously held high positions in society but now were out of power in Jerusalem. This made them feel betrayed and excluded, especially when Jeroboam did not appoint them at Beth-El or Dan. They had no place in Jeroboam’s new religion, and they condemned the golden calves as heresy. The nation was now more divided religiously than ever before, and the political situation was deteriorating rapidly, as the age of empires was coming to the forefront. This left Israel and Judah vulnerable to powerful nations like Egypt and Assyria.

In Israel, the monarchy was unstable, and the kingdom lasted only two hundred years. Then Assyria conquered it in 722 B.C. deporting many Israelites into the Assyrian empire. The exiled Israelites have come to be known as the 10 lost tribes of Israel.

In Judah, on the other hand, the monarchy had been extremely stable, and one of the longest reigning dynasties known in history, which is most likely why Judah survived one hundred years past the destruction of Israel.

During the two hundred years in which these two kingdoms lived side by side, there lived two of the writers that have been identified as J and E. Each of these writers composed their own version of the history of their people, and both versions became part of the Bible. These two versions describe some of the same events, but in different order.

Two of the writers of the first two sources, J and E, lived during those times described thus far. The writer of E came from Israel because he was concerned by matters that occurred in Israel, while the writer of J came from Judah because he was concerned with the events in Judah. Moreover, the group of stories that invoke the name of Elohim are all the tribes of Israel, which lost their territories and merged with other tribes, while the group of stories that invoke the name of Yahweh are the Judah tribe, the only tribe that maintained its territory.