And If You were the Turkish Prime Minister?

The Meeting of the AACF with Mr. Turhan ÇÖmez in Paris

Antoni Yalap

France

"Are you prepared to return to Turkey if the rights and the freedom of the Assyro-Chaldean community are guaranteed by the law? Yes or No!"

"And if you were the Turkish Prime Minister, Mr Adlun, what decisions would you make in favour of your people?"

|

Turkish representative in France, Mr. Turhan ÇÖmez, seen here wearing the Assyrian winged-bull pin, met with the delegation from Assyro-Chaldean community in France on 19 May 2006. |

This is how the Turkish representative of Balikesir, Mr. Turhan Çömez, addressed Mr. Naman Adlun, president of the Assyro-Chaldeans Association of France who was accompanied by a delegation of four in Paris to discuss the demands of the Assyro-Chaldean community of France.

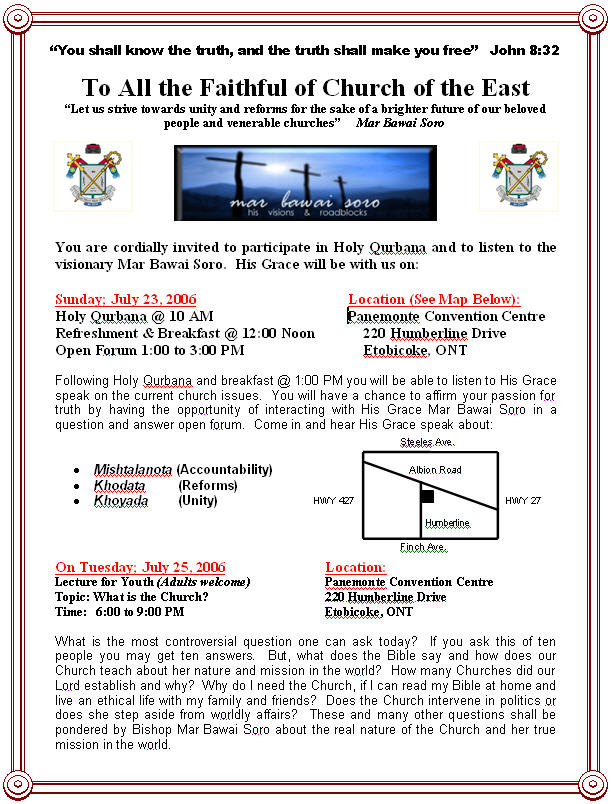

Not long ago, the Assistant to the Turkish Representative in Paris contacted the Assyro-Chaldeans Association of France to schedule a meeting with the head of our community and to speak to us and learn about what we expected from Turkey. A meeting was organized on Friday, May 19th at 11:30 am, in the Hotel K + K in the 7th Parisian district where the Turkish Representative received our delegation led by Mr. Naman Adlun.

The correspondent of the Turkish newspaper, Sabah, and the television channel NTV, Belkis Kiliçkaya, who questioned the Representative prior to the arrival of the delegation, was anxious to assist the meeting and to take some pictures and prepare a report on the Assyro-Chaldeans of France.

The meeting began with the presentation of the book "Göçten Önce" (Before the Exile) by Father Aziz Yalap and the musical CD "Süryaniler" (Syriacs) to the Representative, by the president of the AACF in the name of the delegation.

After the presentations, the Turkish representative talked about the object of the meeting. He asked the usual questions about our community in France: Who are you? How many are you? How long have you lived in France? Why did you come to France?

The answers were not necessarily too appealing to him, because a typical Turkish explanation is that the Assyro-Chaldeans left Turkey for economic reasons. This was not the case. The real answer seems to have raised a problem: the reality of the pressures from the Kurds, the indifference of the Turkish authorities, the political chaos of the 1980s, etc.

And then, suddenly, a surprising question left the delegation speechless: "And if you were the Turkish Prime Minister, Mr Adlun, what decisions would you make in favour of your people?"

The question was not left unanswered for too long . Naman Adlun, by reminding the Turkish Representative that Assyro-Chaldeans are not the enemies of the Turks, explained that he would take the necessary capacities for the recognition of the Assyro-Chaldean identity and the respect for the rights of the community which is not a danger to Turkey, rather a wealth. He explained that these are a people who have for thousands of years only tried to protect their identity, without making any territorial claims. He said: "Our homeland misses us; why could we not spend our holidays on our ancestral land instead of Spain, Italy or Morocco?"

"You are right," answered at once Turhan Çömez, "these lands do not belong to one people in particular. You were there long before any of us. And it is your natural right to live there. What would you say if I provided you with the lands, in the region of your choice, and if I built you very beautiful homes there? You could return to your country, as you wish!".

"Why not?" replied Mr Adlun. "But the Assyro-Chaldeans' cultural, religious, linguistic and historic liberties must be respected and guaranteed. Churches must be built. Opportunities must be organized to guarantee their peace of mind".

These remarks did not seem to shock the Turkish representative, who recognized the importance of respecting and proposed to the whole delegation if his region, very touristy, could be the ideal place for the construction of the flats for the Assyro-Chaldeans.

Very seriously, he promised to speak about this issue to the Prime Minister upon his return to Turkey and asked the president of the AACF about the number of families who would be interested in returning to Turkey and under what conditions.

Additionally the issues of holding double citizenship and the return of the youth to Turkey during holidays or for business, without concern for military service were raised. The representative promised to discuss these issues so that the Assyro-Chaldean youth could settle their cases regarding the military service with the general consulate in Paris.

Regrettably, the very complex question of the recognition of the Genocide was not approached. Nevertheless, it is an essential question which will be necessary to discuss with the Turkish authorities, sooner or later, and cannot be evaded.

The Turkish representative, Turhan Çömez left us after a photo opportunity session. By leaving the delegation, he had affixed to the collar of his jacket, a pin representing the winged bull, the symbol of power, intelligence and dominion.

Middle Eastern Assyrians in the Press

Salim Abraham

New York

Before I took up journalism as a career, I used to often complain to my fellow Assyrians about how our community was under-represented in and ignored by local, regional and international media. The news stories and articles that appeared in Syrian government newspapers such as Tishrin were about ancient “Arab” Assyrians, while international newspapers and news agencies reported on the recent findings of excavations that told stories about the glorious ancient Assyrians. Few media outlets tackled current Assyrian issues despite horrendous atrocities they have suffered from throughout history.

My experience with the Associated Press started in 2001. And the first bylined article I wrote for the AP came on April 1st, 2002, when I reported about the Assyrian New Year celebrations in Syria. To my knowledge, it was the first article on Syrian Assyrians and their political aspirations in Syria that was published by an international news agency such as the AP. After publishing the article and a dozen photos featuring the event, suddenly several Arab and international media offices in Damascus expressed to me their interest in covering upcoming Assyrian New Year festivals. And despite presenting the festival as “Spring Celebrations,” the Syrian official TV aired long clips of footage about the rituals and traditions of the day. However, the London-based al-Hayat and al-Sharq al-Awsat and the Lebanese al-Nahar and al-Safir newspapers picked up the article and photos, showing the real face of the Assyrian festival to their Arab readers. Syrian government doesn't’t recognize ethnic groups, and its press is banned from reporting on minority issues. Since seizing power, the ruling Baath party has followed a policy of Arbizing all Syrian ethnic minorities although they enjoy the freedom of worship.

The suppression of Assyrian issues to reach international media outlets seems to be grounded in history. A ProQuest search of major American newspaper archives from 1851 to 2003 for the word, “Assyrian,” produced only 8304 hits, 75 percent of which were news relating to relics and excavations. To take Kurds, who have coexisted with Assyrians in neighboring areas in Iraq, Turkey, Iran and Syria for centuries, as a parameter to gauge media coverage of Assyrians, the word, “Kurd,” retrieved about 19638 hits. We have to take in mind that Kurds lack historical records before 11th century as historians agree that they have lived a nomadic life until the Ottomans started settling them in northern Mesopotamia, the land between the two rivers.

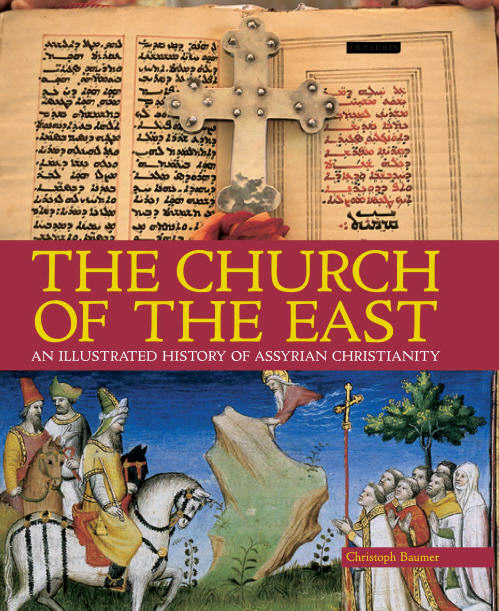

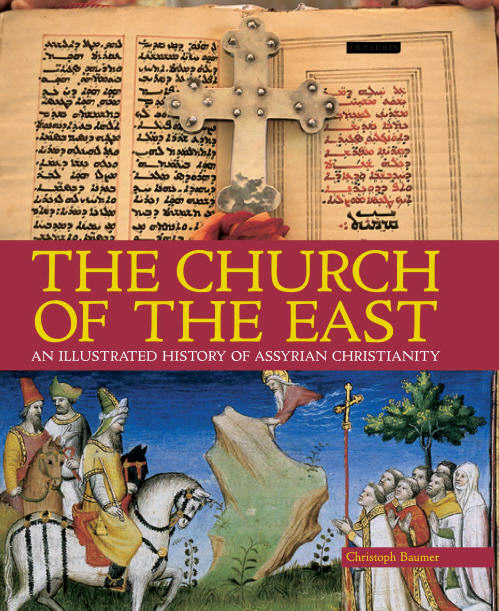

An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity |

|

20% off List Price for

ZINDA READERS

For a limited period only & only for readers from U.S.

View Zinda Info: Click Here

Click Bookcover to Order Your Copy

Use Promo Code P356ED

when you proceed to 'Checkout'

|

|

The small number of the archived stories is an evidence of the successive Middle East governments’ success in suppressing news about their atrocities against the Assyrian people, who – through slaughtering them and driving them out of their homelands – have been reduced to a minority of 1 million people in their home country, Iraq. Salim Mattar says in his Arabic-language book The Wounded Lion that Assyrians represented about 60 percent of the Iraqi population at the end of the Abassid Caliphate in the thirteenth century. The Iraqi Shiite writer, Mattar says that Iraq’s population was estimated at about 11 million people.

The Assyrians once dominated the Middle East. In the 7th century B.C., their empire stretched from today’s Iraq through southern Turkey to the Mediterranean. They were among the first converts to Christianity and are divided into several churches, including the Catholic Chaldean, the Syriac Orthodox and Catholic and the Church of the East.

More recent number of Assyrians in the region came from Ottoman records. Yusuf Malek, a Chaldean-Assyrian writer, says in his book The British Betrayal of Assyrians that Assyrians of Mesopotamia numbered about 1 million people, Kurds were estimated at 1.2 million and Iraq’s Arabs were barely 2 million people the year before the World War I. Now the number of Assyrians in Iraq remains the same a century after that Ottoman census. Kurds number about 3.5 million and the rest of Iraq’s 25 million people are Shiite and Sunni Arabs, Turkumen, Yezidis and Shabak.

The huge pressures, both ethnic and religious, on Assyrians explain why this Christian minority’s expatriates now outnumber those at home. And Despite that the Assyrians have been oppressed by rulers in the distant and near past, Assyrian issues have been barely reported in American major newspapers. Time and again, Assyrians had to flee to neighboring countries and to places as remote as Australia, New Zealand, Europe and the United States or face both religious and ethnic pressure at times of tyranny and unrest in their homelands.

In October 2005, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees reported from its Damascus office that approximately 250,000 Christians have been driven out of Iraq by the factional violence since Saddam Hussein was toppled in March 2003. According to a UNHCR report, Christians make up about half of the Iraqi refugees in neighboring Syria. The report was only picked up by Agence France Press and by a few Arabic-language media outlets, such as the well-known Elaph web site, www.elaph.com. No major American newspaper reported the recent displacement of Chaldean-Assyrians. Lexis-Nexis and Factive search for the words Assyrian and UNHCR retrieved no hits.

A Google news search for the word, “Assyrian,” retrieved only 221 hits in the period between April 1 to May 6, 2006, while the word, “Kurd,” had 12,500 hits in the same period. It’s also noticeable that about 60 percent of the “Assyrian” hits were news relating to archeological findings and looting. The media coverage ratios of Assyrians to Kurds show how international media and political agencies are pushing Assyrian issues into oblivion given that Assyrians are Iraq’s third largest ethnic group.

The recent Christian exodus is the largest since 1914, when the Ottomans slaughtered about 1.5 million Armenians, 750,000 Assyrians and 350,000 Pontiac Greeks and drove hundreds of thousands of Christians out of their homelands. Although American public has known Assyrians through the bible and through the missionaries in Assyrian areas since the 17th century, the atrocities of the 1914-1918 perpetrated by Ottoman Turks were not enough to attract the attention of major American newspapers. A ProQuest search for “Assyrian” between Jan. 1, 1913 to Jan. 1, 1920 produced only 478 articles in newspapers, such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune and the Boston Globe, while at the same time the search for the word, “Armenian,” produced 5755 ProQuest hits. The word “Kurd” had 1628 hits. One might attribute this insignificant presence of Assyrians in American newspapers to the lack of American readership interested in Assyrian issues or to the small size of the Assyrian community in the United States. But American Assyrians have always outnumbered Kurds in the U.S. a great deal. Today, Assyrian Americans are estimated at 450,000 people, while Kurds in the U.S. are no more than 15,000 people.

However, it seems that an incident in which an American mission protecting Assyrians in Persia received a considerable attention. The Washington Post’s correspondent William T. Ellis, reported on July 15, 1919, from Constantinople (today Istanbul) on Turks’ and Kurds’ attacks against the American Presbyterian mission in Urmia, a western town in Iran.

“Here is a tale of heroism and horror and of historic human interest that would have challenged the whole world’s attention five years ago,” Ellis said. “Now I fear that it will make scarcely a dent upon war-calloused consciousness of mankind.”

“Urmia, in western Persia, for nearly a century a center of American mission work, latterly a relief base, and the seat of the remnant of the ancient Assyrians, who now commonly are called Nestorians, or Syrians, has again been devastated, and the only Christians left are in captivity or in hiding,” said Ellis. He continued: “Less than 1,000 Christians had been left alive in the city last spring, after repeated attacks from Kurds, Turks and Persians, and these Christians had again taken refuge behind the American flag, which had once before saved them from hostile Turks and Kurds.”

Ellis reports that more than 200 Assyrians were massacred in another incident and 30,000 others fled their homes to Russia and Baghdad. At the time, Urmia’s all-Assyrian population was 40,000. The massacre received the attention of all major American newspapers at the time mainly because of the attack against the American missionary. The New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, the Boston Globe and other publications reported the same incident quoting U.S. officials in the region. Ellis also said there were “many thousands of Assyrians in the United States, especially men, and to these the nation will look for perpetuation.”

Those massacres would not halt until 1924, four years after the British and other European powers broke down the vast Ottoman Empire into states under their mandates. Iraq and the Assyrians fell under the British mandate in 1920. Religious and ethnic tensions in the predominantly Muslim region continued for decades.

In August 1933, months after Iraq gained independence from Britain, the massacre of 3,000 Chaldean-Assyrians at the hands of the then-Iraqi government in Simile, a small Assyrian town near Mosul, prompted the displacement of about 34,000 of them. The Iraqi government newspapers suddenly raised Assyrians to media prominence. They published about 382 articles calling on Iraqi Arabs and Kurds to wage Jihad – or holy war – against Christian Assyrians during the month leading up to the August massacre. If the Iraqi drive to massacre their fellow Assyrians leaked into international media, the massacre might have not happened. But international media attention took the massacre itself, and the Chaldean-Assyrian problem was referred to the League of Nations. Hundreds of articles tackling the massacre and its repercussions on Assyrians were published in the then-major British newspapers, according to Malek. The issue has also gained the American newspapers’ attention. A ProQuest search from 1933-1935 for “Assyrian” retrieved 261 hits, with many commenting or reporting on the massacre. During the same period of time, ProQuest search for “Kurd” retrieved only 244 hits. The majority of the “Assyrian” hits covered the massacre.

The Chicago Daily Tribune’s John Steele report on Aug. 16, 1933 from London was headlined “800 Assyrians Slain in Iraq; Britain Aroused. King Feisal Is Ordered to Halt Massacre.”

“The British foreign office was seriously concerned today by news from Iraq that the number of Assyrians slain by Iraqi irregulars in the last few days had reached a total of eight hundred,” Steele wrote in his lead paragraph. “Many more Assyrians have been placed in a dangerous predicament as a result of the destruction of their villages.”

The AP followed up from Baghdad. “Baghdad cheers as troops return from war on Assyrians” was its Aug. 26, 1933 story headline on the massacre.

“To the strains of ‘Marching Through Georgia,’ played by an Arab military band, Iraq Moslem troops marched through Baghdad today on their return from successful operations against Assyrian Christians,” wrote AP’s reporter. “They were acclaimed by a widely enthusiastic populace. The whole city seemed to have given way to a frenzy of excitement. Old time residents said such scenes had not been witnessed in the capital within the memory of the living.”

The AP reporter continued: “The troops were preceded on the march through the city by thousands of admirers, some of whom carried big sticks while others waved daggers.”

In the years that followed the massacre, articles on Assyrians would only be about the achievements of their ancient forefathers although major events have never stopped to happen in the Middle East. Arabic-language newspapers ignored – as they still do – their issues as a way to avoid blaming their governments for the dwindling numbers of Chaldean-Assyrians. Not even the 1991 first Gulf War could drag some attention to this ancient minority. A Lexis-Nexis search for the word “Assyrians” from 1990 to 1993 retrieved only 53 hits, while the same search for the word “Kurd” retrieved 1255.

In Syria, since the Baath Party took power in 1963, the Syrian authorities have tried to subdue non-Arab minorities, especially Assyrians and Kurds, through the notorious policy of Arabizing even the stones under the surface of the ground. Our parents were not allowed to have Assyrian names for their children until early 1970s.

But the darkest days of Syria’s minorities and opposition parties, in general, came after Hafez Assad seized power in 1970. All political parties, including minority ones, went underground. And prison was the fate of whoever opposed the regime, while media censorship grew tighter and tighter. Fear prevailed all over the country especially in mid and late 1980s.

In 1986, the 22 members of the Assyrian Democratic Organization’s (ADO) leadership were arrested in Syria. Nothing appeared in newspapers or in any media outlets about the arrests, apparently, because the regime had control over even the Syrian correspondents of foreign media in Damascus.

|

Three leaders of the same organization were arrested in 1990s for raising funds to provide clean water for 36 Assyrian villages, which had been deprived of the waters of Khabour River in northeastern Syria after building a dam on it. It was so clear that the dam was meant to take the water from those poor Assyrian villagers to Arabs living as far as a hundred kilometers from the water sources. Once again, not a single article appeared in major newspapers despite the fact that Assyrians in the Diaspora could have turned this particular issue into a cause that world public opinion could not ignore. The water problem led to another wave of immigration from those villages to the nearby city of Hasaka and to the West. Nowadays, the farms are being sold very cheaply and some villages have been almost totally emptied.

After the death of Hafez Assad in June 2000, a new era in Syria’s political life was emerging. Apparently, the heir of the presidency, Bashar Assad, Hafez’s son, has shown his willingness to change the image of Baath legacy in repressing Syrians since he assumed office a month after his father’s death. He has marketed himself as an open-minded Baathist who might recognize his political rivals and tolerate dissent. As a sign of openness, Assad has ordered the release of hundreds of political prisoners and has issued hundreds of laws aiming at liberalizing the country’s socialist-style economic system.

In that atmosphere, political discussion salons spread like mushrooms all over the country. Syrian intellectuals freely discussed issues ranging from corruption of the Baath rule to minority issues. Assyrians rarely attended such forums. Consequently, their issues were rarely present.

Soon afterwards, Assad ordered the crackdown on those salons and political and human rights activists were arrested. The so-called “Damascus Spring” was put to a halt. But voices of change grew louder also, especially after the U.S.-led war that toppled the Iraqi dictator in March 2003.

Since then, the region has witnessed unprecedented changes. Syrians, including Assyrians, grew more impatient with the totalitarian Baath rule than ever. For the first time in Syria’s Assyrian history, about 2000 of them took to the streets in October 2004 to protest the killing of two fellow Assyrians at the hands of two Arab brothers, who insulted their victims as “Christian dogs.” The demonstrators demanded for justice and law to prevail.

The demonstration was widely covered by major foreign and Arab media, but not by local government newspapers or Radio and TV channels. Tens of Arabic-language newspapers ran the news on the Assyrian demonstration. Yet I couldn’t report on that important event in spite of my efforts to do so obviously because the manager of the AP office in Damascus was ordered by secret police to prevent any reports about the demonstration from being published in international newswires. However, I was able to help some foreign journalists, including a New York Times reporter, to write about this issue.

Just a few months earlier, I wrote two reports for the AP telling the story of how the Syrian authorities prevented the ADO from celebrating its anniversary and marking the Assyrian Aug. 7 Martyr Day, on which Assyrians around the world commemorate the massacre of the 1933. The two reports prompted several foreign diplomatic missions in Damascus to reach out to the organization in order to know more about Assyrians in the country.

Also after the Iraqi war, thousands of Iraqi Assyrians from different denominations were fleeing the violence in their country. The exodus was most remarkable in the summer of 2004, the thing that led me to observe closely the life of the Iraqi Assyrian refugees in Damascus for months. I decided to write a report about the phenomenon for the AP and soon after being on AP’s newswires on Aug. 4, three days after the church bombings in Baghdad and Mosul, the report was picked up by as many as 12,000 newspapers around the globe. As a result, the issue was discussed by parliaments of several western countries, including Britain, Australia and the United States. And eventually, international media, including American, could sense that a real 21st century Assyrian problem was looming. A Lexis-Nexis search for “Assyrian” during August of 2004 retrieved 54 hits, while same search for the word “Kurd” had 135 hits.

After media attention to Assyrian issues picked up Turkey’s Assyrians were in the media spotlight also. The Turkish Rajab Tayeb Urdogan’s government allowed them to celebrate the Assyrian New Year for the first time in their recent history. And the New York Times ran an article completely on Assyrians, after their reporter in Syria decided to accompany me more than a thousand kilometers to the southeastern Turkish town of Medyat to cover the festival. The article was run also by the International Herald Tribune, Houston Chronicle and other newspapers.

The coverage that Turkey’s Assyrian New Year celebration received in diverse publications came late as Assyrian numbers plummeted to only 6,000 people from hundreds of thousands at the beginning of 20th century.

|

But despite the media attention Assyrians have received lately, American publications are still reluctant to report major prejudices against them. In February 2005, for example, the English-language Assyrian International News Agency (AINA) reported that an Assyrian from Bartelleh, the overwhelmingly Syriac Orthodox town in northern Iraq, has been killed by KDP Kurdish militiamen who were trying to steal gasoline from a public fuel station there. This is a newsworthy incident in its own right, and there are signs that the crime was even ethnically-motivated. But how many newspapers, Iraqi or international, reported it? None. Surely, there are many journalists working in Iraq and elsewhere who are interested in human rights. But when such abuses are perpetrated against Iraqi Assyrians, why are they so rarely reported?

The reason behind that is not to be blamed on foreign media outlets only. It can be also traced to the dearth of journalists among Chaldean-Assyrians. It partially explains why the murder of the Iraqi Assyrian was not reported by any major media means.

Last year also, Assyrians’ protests and demonstrations against the Iraqi draft constitution which unfairly misrepresented them through splitting them into more than one ethnicity represent another shocking example of the lack of Assyrian reporters in Iraq.

Prominent Assyrian journalists such as Nuri Kino and Jameel Rofael, of the Chaldean Church who has reported from Czech Republic for al-Hayat newspaper for years, have contributed to raising the awareness of the public opinion in their countries of residence about Assyrian causes. But two or three journalists around the entire world are too few to showcase a cause. Out of three million people, Assyrians have less than ten professional journalists around the world and no professional journalistic institution that is capable of addressing their own causes, despite the dozens of cases of repression Assyrians of the Middle East have been suffering at the hands of successive governments there. It’s worth noting that one of the earliest Middle East publications – if not the earliest – was Assyrian. The weekly Zahrira d Bara – or Ray of Light – started running from 1851 till 1914 in Urmia, Iran. The magazine certainly was the first publication in Iran.

Yet the lack of journalists cannot explain the whole problem of media coverage of Assyrian issues. On Jan. 29, six churches were bombed in Baghdad and the northern city of Kirkuk after a Danish newspaper published cartoons ridiculing Islam’s Prophet Muhammad. A 13-year-old Assyrian and a Muslim couple were killed in the Kirkuk bombing. American major newspapers kept silent over the incident at a time when the Muslim world was raging with demonstrations and protests, burning flags and embassies of Denmark and other European countries. A Lexis-Nexis search for the words “Assyrian and Kirkuk and church bombing” yielded only two hits both run by the AP. Attacks on churches in Egypt, Pakistan and elsewhere by Muslim protesters were well covered, though. The little media attention the Kirkuk church bombings received can be ascribed to political reasons.

Apparently, American media wanted to send a message to Islamic world that American presence in Iraq is not to support Assyrians, who are always seen by Muslims as supporters of the West. Also it can be a message that American wars against global terrorism are not a crusade against Islam.

Certainly Assyrians have received some attention of American, Arabic and international media in the last three years since the U.S.-led war on Iraq. Yet they haven’t received their fair share of media coverage. Their problems continue to be important. Prejudices continue to be perpetrated against them. Their political power is too insignificant to force their fellow countrymen to recognize their unsolved problems, such as the villages from which they were evacuated by Kurds in northwest Iraq on the border with Turkey in the 1990s. Although the world has other horrendous humanitarian problems, such as that of Darfur in Sudan, Assyrians of the Middle East deserve to be heard, as well.

Mr. Salim Abraham is completing his graduate studies in journalism at Columbia University in New York and writes for the Associated Press. Mr. Salim has previously written about the Assyrians in Syria and elsewhere for Zinda Magazine and consults this publication on reporting from that region. Mr. Salim Abraham is completing his graduate studies in journalism at Columbia University in New York and writes for the Associated Press. Mr. Salim has previously written about the Assyrians in Syria and elsewhere for Zinda Magazine and consults this publication on reporting from that region.

Living in a Virtual Nation

Courtesy of SBS Radio’s latest publication, ‘Speaking My Language - Thirty Years of SBS Radio.’

It was the first week of the ongoing war in Iraq, and the Assyrian Aid Society (Iraq) was begging for help. Wounded, starving and freezing villagers were caught in the middle of the bombing, the fighting, even the looting.

The plea went out across the Internet to the society’s branches in Australia, New Zealand, the United States, to the far corners of the world.

Within days, David Chibo remembers, the Australian branch collected $35,000. New Zealand came up with another $10,000. The United States, heartland of the Assyrian diaspora, sent $200,000.

“At a time when our people needed humanitarian aid, we didn’t have to beg strangers, or wait for them, to help,” he says proudly. “Ultimately, it saved numerous lives, largely because of the medicine, but, also, if the people had food and blankets, they didn’t have to journey out and risk being bombed in the search. So it was preventative medicine, too.”

|

David Chibo at the British Museum standing before an Assyrian stela. |

If it was preventative medicine for Assyrians in Iraq, it was also a strong dose of feel-good medicine for the native Melburnian and his kind around the world. They are the Assyrians of the diaspora who have become linked to the land of their ancestors like never before – via the Internet.

For a people with no country of their own, a people where two in three are believed to be scattered around the world, it was a moment of unity. It was proof that, in the 21st century, the Assyrians at least have, in a sense, a virtual nation.

“Coordination along these lines was impossible before the Internet,” Mr Chibo says, relaxing at an Assyrian restaurant nestled amid the Middle Eastern eateries on the main strip of inner-suburban Brunswick. “The Internet has gathered Assyrians dispersed throughout the Western world and the Middle East.

“It’s given them a focal point where they can gather together in cyberspace and interact,” he says, “where they can read news of what’s happening in the homeland as well as overseas, where they can exchange ideas, where they can politically challenge each other, where they can grow. The Internet has transformed Assyrian politics and Assyrian society.”

To say Mr Chibo is relaxing is to stretch the word to its limit. The burly Telstra engineer’s well-worn blue jeans and casual, long sleeved T-shirt belie an almost feverish intensity when it comes to his people. He leans forward far more than he leans back, and his eyes leap at the listener, much like his words.

At age 33, it’s an intensity born of, already, a quarter of a century working out just where he comes from. It was his early school days when he first noticed his skin was a shade darker than his classmates’. Why, he wondered. Who am I? What’s my story?

He set out to learn his history – not easy when he couldn’t even find Assyria on a map.

What he found was a culture more than 5,000 years old that, at its height, covered parts of nine countries in today’s Middle East. Iraq was the ancestral home, specifically an area called the Assyrian Triangle, along the Tigris River.

Most estimates suggest around a million Assyrians still live in Iraq, with possibly two million more spread around the world. The Assyrian language has bound them together, along with their religion – Assyrians were among the first to accept Christianity.

“The whole discovery search has allowed me to define myself, to understand where I stand and what I hope for the future,” Mr Chibo says. “It’s a little bit tough to be a minority in Australia and then realise you’re a minority in your ancestral home as well, but it’s forced me to apply myself more.”

DAVID YOUKHANA

|

|

ARIZONA

Real Estate-Relocation-Investment |

|

Broker / Owner

Certified Commercial Sales Specialist

Babylon Realty

Glendale, Arizona 85310

Click Photo For More Information |

602-410-9555

|

|

He has applied himself, above all, to giving back to that culture. The year before the war, he spent four months in northern Iraq helping the Australia’s branch of the Aid Society do wide-ranging community work. He is the Australian representative for Internet-based Zinda magazine, the premiere publication in the Assyrian world.

He has attended conferences as an Australian community representative in both Iraq and the United States, where Chicago alone has more than 80,000 Assyrians. Mostly, he was putting faces to names, the names from cyberspace.

They are the fellow activists from around the globe he converses with late into the night, debating the Assyrian world’s political and social issues on the online forum PalTalk. It’s there that the Assyrian news is dissected piece by piece.

“Because of the Internet, it’s SBS Radio’s Assyrian program that is very famous out there, in places like Chicago, in Iraq,” Mr Chibo says. “They have radio programs in Chicago where they take (the SBS) interviews and broadcast them on their own programs, because, with the resources of SBS, they’re actually able to contact people throughout the world.

“The volunteer radio programs, they can’t afford to do those interviews,” he says. “And they’re not as professional, min you. So since SBS is putting them on the Internet, and with their permission, there’s a large dissemination of these interviews around the world.”

Key Assyrian web sites, like Zinda, link to the program, too. It’s all part of the new flow of information and comment binding the world’s Assyrians.

Mr Chibo jokes it is leading to a community starved for knowledge but drowning in information. Then more seriously he talks of a people becoming less parochial, more aware both at home and overseas. He talks of the Internet triggering a renaissance of the Assyrian culture, reviving a 3,000-year-old language from the brink of extinction.

He talks of community leaders, be they politicians or priests, knowing they face scrutiny now. He talks of a culture of hiding things, of sweeping them under the rug, is being forced to change, with the community changing in turn.

But unlike so many activist movements, none of the change is aimed at achieving an independent state. As Mr Chibo gazes around the empty, spacious restaurant surrounded in a blue-and-gold Middle Eastern décor, he struggles to put into words just what the goal is.

“In the long run here,” he says finally. “I think we just want to better our people and our community, as well as provide a rich tapestry for all off Australian society.

“What we seek to preserve in our culture, our language,” he says, “is a precious part of the Australian society.”

What sets Zinda Magazine apart from any other Assyrian, or for that matter Middle Eastern magazine, is that it allows its staff to apply themselves to investigative and opinionated writing which may or may not agree with the central views of the majority of its readers and often its editor(s). Mr. David Chibo's investigative reporting from Australia has in the past shaken the foundations of the most revered Assyrian political parties, organizations and churches. Likewise, every week Assyrians in Australia are also invited to hear Mr. Wilson Younan's piercing and relative questions on his weekly radio program on SBS Radio (click here). Only through this type of professional and edifying journalism the public is inspired to demand accountability from its civic, political, and religious leaders. What sets Zinda Magazine apart from any other Assyrian, or for that matter Middle Eastern magazine, is that it allows its staff to apply themselves to investigative and opinionated writing which may or may not agree with the central views of the majority of its readers and often its editor(s). Mr. David Chibo's investigative reporting from Australia has in the past shaken the foundations of the most revered Assyrian political parties, organizations and churches. Likewise, every week Assyrians in Australia are also invited to hear Mr. Wilson Younan's piercing and relative questions on his weekly radio program on SBS Radio (click here). Only through this type of professional and edifying journalism the public is inspired to demand accountability from its civic, political, and religious leaders.

|